The Shinkolobwe radium mine, 1922. The Belgian mining engineer above is sitting on a 7 ton boulder of pitchblende. An immense quantity of gamma-rays is irradiating his gonads. Safety equipment, a tie and a pith helmet.

Unknowable to to the engineer, the rock contained enough uranium 235 to make a couple of atom bombs. However, uranium was a by-product in 1922, having only a little demand within the glass and ceramics industries. At Shinkolobwe, they were mining radium, worth 30,000 times more than gold.

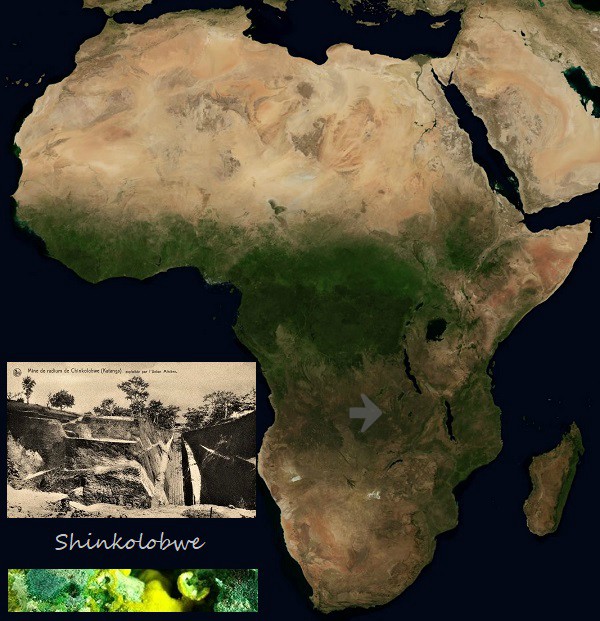

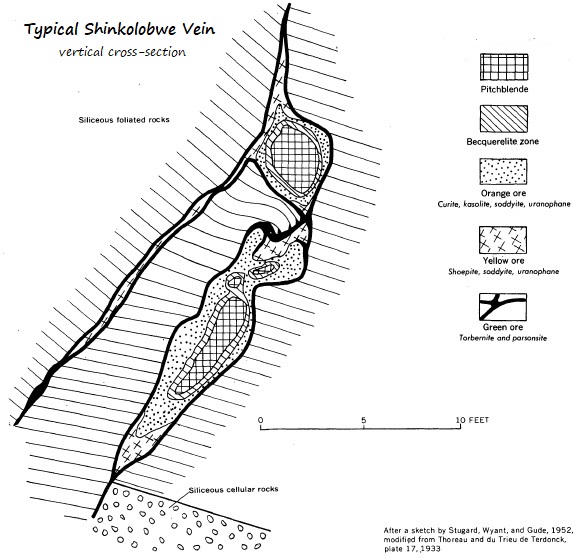

Deep in Darkest Africa, Shinkolobwe is a radiological mineral phenomenon. With a plethora of colourful secondary uranium minerals (it’s the type locality for 38), the mine also has large veins of pitchblende, crystallised in parts with uraninite (UO2) cubes to 4cm. It’s situated in the Katanga province of the Belgian Congo, which hosts the “copper crescent,” with mines unearthing 220 minerals, including 64 type locality minerals.

Below, a zoomable view of Shinkolobwe, source of great wealth, beautiful mineral specimens, and over 100,000 deaths.

Shinkolobwe Uranium Secondaries

Shinkolobwe Uranium Secondaries

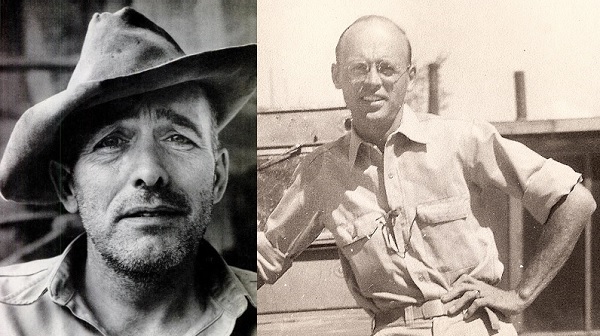

In 1915 a bloke born in Gateshead, Co. Durham, had blagged himself a job prospecting in the Congo for a particularly dodgy outfit, the Union Minière du Haut Katanga. Robert Rich Sharp (1881–1960, below) had graduated from Oxford with a classics degree, took a couple of classes in geology, and began scouring the copper crescent of Katanga for new mineralisation.

He’d heard stories of natives daubing their bodies with brightly coloured “ochres” near the small village of Shinkolobwe. The settlement’s name means “fruit that scalds.” Sharp climbed a nearby hill, on the lookout for green copper secondary minerals. What he discovered though, was bright yellow and orange mineralisation. Fortunately, he’d seen uranium minerals in a museum, identified the deposit as such, and thought “Radium!”, then the most valuable substance on earth.

His Belgian bosses, the Union Minière du Haut Katanga, knew a thing or two about forced labour and shortly open-cast mining uncovered a large veins of very pure pitchblende -

Soon they got serious, with a thousand strong workforce -

Shinkolobwe was such a rich deposit of ore, that it closed down in 1937 because “enough ore had been stockpiled to cater to world demand of radium and uranium for the next 30 years.”

Otto Hahn discovered nuclear fission a year later.

Soon, with a World War taking place, the Americans needed all the uranium they could lay their hands on. The Manhattan Project meant that uranium had suddenly become a strategic material, no longer a by-product from radium extraction, and of use only to make green glass and yellow glaze.

Here’s an account of the mine, written when radium demand had plummeted, and uranium had become the new most sought-after element -

From Minerals for atomic energy, Nininger, 1954

From Minerals for atomic energy, Nininger, 1954

Union Minière du Haut Katanga had stashed 1200 tons of prime Shinkolobwe ore at a warehouse on Staten Island, USA, before the war. The man in charge of raw material procurement and processing of U235, Colonel Ken Nichols, had this to say about the Congo mine after the war -

“Our best source, the Shinkolobwe mine, represented a freak occurrence in nature. It contained a tremendously rich lode of uranium pitchblende. Nothing like it has ever again been found. The ore already in the United States contained 65 percent U3O8, while the pitchblende aboveground in the Congo amounted to a thousand tons of 65 percent ore, and the waste piles of ore contained two thousand tons of 20 percent U3O8. To illustrate the uniqueness of Sengier's stockpile, after the war the MED and the AEC considered ore containing three-tenths of 1 percent as a good find. Without Sengier’s [CEO Union Minière] foresight in stockpiling ore in the United States and aboveground in Africa, we simply would not have had the amounts of uranium needed to justify building the large separation plants and the plutonium reactors.”

The Staten Island ore was bought by the US government, as was 3000 tons stockpiled at the mine. The uranium ended up in the Y-12 calutron at the Oak Ridge uranium enrichment facility. The cost of the raw materials from Shinkolobwe was rather minimal compared with the overall expense of electromagnetically separating U235 from the common U238. The Y-12 calutron used 430 million troy ounces of pure silver (value £4.8 billion) as high conductivity wiring.

Using 64 kg of Shinkolobwe uranium, enriched at Oak Ridge to 80% U235, the bomb “Little Boy” was constructed and dropped on Hiroshima, August 6, 1945. 50,000 civilians were killed instantly.

Following this horrendous use of nuclear power, the Cold War ensured continuing demand for uranium. Shinkolobwe was reborn as a uranium mine, with global importance - in 1954 a government decree, “authorised the shooting on sight of any persons found within the boundaries of the Shinkolobwe uranium mine, who had no right to be there.” By 1958 sophisticated weighing and scintillometer gear was in place to monitor uranium concentration (below). Union Minière du Haut Katanga made many tens of £millions from the mine, while the native workers suffered cancers and birth defects. Even the European bosses, the tie and pith helmet brigade, although having little daily contact with the highly radioactive ore, succumbed to cancers - three died in their 40s. Shinkolobwe was, and still is, one of the most deadly places on earth.

Strategic materials procurement became a big issue within the United States. They could not rely on a monopoly company like Union Minière du Haut Katanga to supply uranium. The Belgian Congo was reaching social detonation point after so many decades of exploitation. In 1960 the country gained independence, but corruption and conflict caused rapid decay of infrastructure, and the Shinkolobwe mine closed.

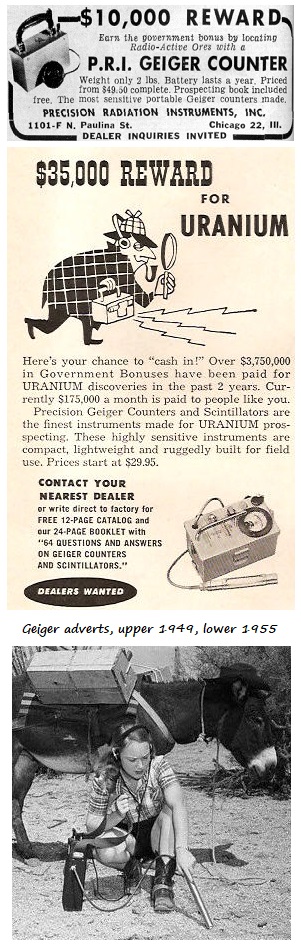

With this sort of future envisaged for the Belgian operation, the US had desperately sought a source of uranium within the States from the start. In April 1948 the just created AEC (Atomic Energy Commission) announced massive rewards, bonuses and guaranteed prices on domestic uranium finds.

$10,000 was offered for “the discovery of a new deposit and the production therefrom of the first 20 short tons of uranium ore or mechanical concentrate assaying 20% or more uranium oxide.” plus $3.50 paid per pound of uranium oxide.

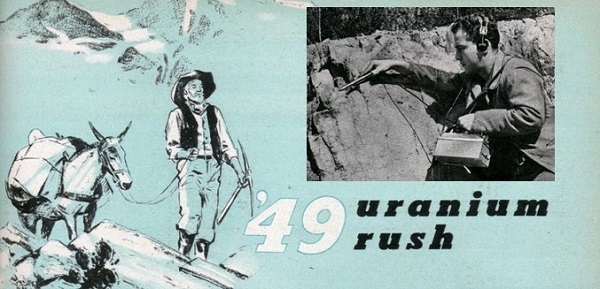

A Uranium Rush ensued, with 30 times more folk involved than during the Gold Rush, one hundred years before. The rushers had government printed instructions on uranium prospecting, and more equipment than the original ‘49ers -

Above, a young lady prospector with geiger counter and a nice ass.

Above, a young lady prospector with geiger counter and a nice ass.

The Colorado Plateau Carnotite Connection

The Colorado Plateau is an area of high desert within western Colorado, northwestern New Mexico, southern and eastern Utah, and northern Arizona, USA. The huge area of sedimentary rocks is host to the potassium uranium vanadate mineral above, carnotite.

Ute and Navajo native americans used the bright yellow carnotite as war-paint and to colour buckskins, but the mineral first came to the attention of science in 1881. Prospector Tom Talbert sent some mineral samples he’d found in the Roc Creek area of Montrose County to Leadville for analysis. The assayer was unsuccessful in determining what elements were present in the crumbly yellow mineral in its sandstone matrix. The analysis required a good chemist.

In 1896 Gordon Kimball and Tom Dullan took over the Roc Creek claims and in 1898 sent specimens to chemist Charles Poulot, a graduate of the University of Paris (Sorbonne) School of Mines. He identified uranium, but for its further analysis he sent samples to his former mentor, Professor Friedel at the Sorbonne.

Pleased with knowing their claim had a mineral of utility for the glass and ceramics industries, Kimball & Dullan shipped 9 tonnes of the unknown mineral to Denver in June 1898, receiving $260 for it. It contained 21.5% uranium oxide. They weren’t to know that their mineral also contained a new element, discovered by Marie Curie in the same year. Had they held on for a few years….

Meanwhile the French mineralogists Charles Friedel and Eduard Cumenge investigated the samples Poulot had sent them. They published their results in Comptes rendus de l'Académie des Sciences in 1899. They named the new mineral Carnotite, K2(UO2)2(VO4)2·3H2O, after the french chemist & mining engineer Marie-Adolphe Carnot (1839 – 1920), nephew of Sadi Carnot, "father of thermodynamics," of Carnot cycle repute.

Carnotite only very rarely presents good crystals. The above specimen (with associated minor yellow tyuyamunite, from a mid 80s find) is from Mashamba West Mine, Katanga, Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Colorado Plateau material is disseminated through sandstones as powdery encrustations (below on fossilised wood), or as nodular concretions.

Carnotite, containing the valuable elements uranium, vanadium and radium, was to be a mineral targeted by three eras of mining interest -

The Radium Boom

“From 1910 to 1923, the carnotite ores are estimated to have yielded 202 grams of radium with small amounts of vanadium and uranium recovered as byproducts. During this period, the price of the world market for the elemental radium content in purified salts, ranged from $70,000 to $180,000 per gram.” Chenoweth, 1981

The Colorado Plateau radium boom ended with Robert Rich Sharp’s discovery of Shinkolobwe. The Katangan pitchblende deposit was of such phenomenal richness that it made mining carnotite uneconomic, with the last mines and mill closing in 1923. Things would soon fall apart with the worldwide radium boom, after it’s extreme toxicity was brought to light by the Radium Girls and a wealthy American socialite’s jaw dropping off.

The Vanadium Boom

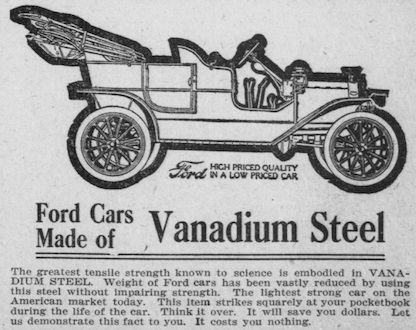

Henry Ford’s Model T exemplified the need for vanadium -

The assets of the Colorado Radium Company and the Radium Luminous Metals Company were acquired by the Vanadium Corporation of America (VCA) in the 1930’s. The old radium mines were reopened, the waste tips worked over. Vanadium was in demand, and this would dramatically increase with the advent of WW2, becoming a strategic material in 1942. However it’s importance was soon overshadowed by its fellow element in carnotite….

The Uranium Boom

Two guys who chanced their luck at finding uranium were lone prospectors Vernon Pick (left) and Charles Steen. Both at the end of their respective financial tethers (dirt-poor), Vernon shelled-out his last dollars on a scintillometer, and Charles a diamond drilling rig. Vern struck in big in 1953, Charlie in ‘52.

Vernon Pick was a self taught prospector. After years of failure, he had “one last go” and decided the canyon of the Muddy Creek, near Hanksville, was worth a shot. Carrying a 65lb backpack, he hiked alone 25 miles into the wilderness. For one six-mile stretch he had to ford the creek 21 times. Drinking Muddy Creek water poisoned him with arsenic. He had a rest...

His scintillometer red-lined. He thought it was faulty until he broke some rock. His first hammer blows revealed thick deposits of bright yellow Carnotite. At the end of the first year, his Delta mine (later renamed the Hidden Splendour) had produced 300,000 tons of ore selling at $40 per ton. Vernon, already a millionaire, sold his mine in ‘54 for $9m. After paying tax, Vern pocketed, in today’s UK money, £42.5m.

Charlie Steen was a petroleum geologist who had been fired by the Standard Oil Company for insubordination, subsequently black-balled by the US oil industry. He decided uranium prospecting was the way to go, and moved the family to near Moab, Utah -

He didn’t have a scintillometer, or even its less sensitive cousin, a geiger counter. All he had was a madcap notion that uranium deposits would collect in anticlinal structures in the same manner as oil (dismissed by fellow miners as "Steen's Folly"), and the ability to drill core with his second-hand diamond rig.

Charlie reckoned that he’d know when he hit uranium, when the yellow mineralisation of carnotite was present in the drill-cores. He’d been bitterly disappointed with his last drilling - starting on July 6, 1952, at Big Indian Wash of Lisbon Valley, southeast of Moab, Utah. On July 27th, the drill-bit broke off at 197 feet, and he stopped. None of the cores showed yellow mineralisation, although the sandstone had appeared coal-black for 14 feet on the 6th, at a depth of 73 feet.

Three days later he was fuelling his vehicle and asked his friend, the service station owner, to quickly run his geiger counter over the unusual black cores in the back of the jeep.

His geiger counter red-lined. Charlie had drilled through a 14 feet thick vein of pitchblende. There had been no significant finds of pitchblende in the Colorado Plateau until this moment. Occasionally the mineral had been encountered as a replacement mineral in fossil wood, but what Charlie found was a true bombs bonanza. All of the production from Charlie’s Mi Vida mine went into atomic weapons, as US commercial nuclear power didn’t begin until 1957.

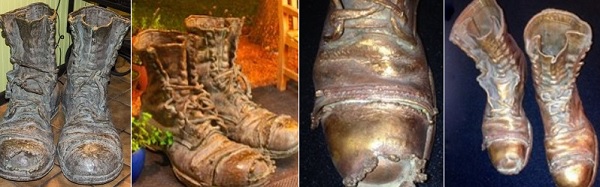

Charlie became a multimillionaire, mining stuff to make things that no-one wanted to use. His great fortune enabled him to have three-feet high bronze replicas of his boots cast. He died penniless.

References -

Manhattan, the Army and the atomic bomb, Vincent C Jones, 1985

Prospecting for Uranium. The United States Atomic Energy Commision & The United States Geological Survey, 1949

Minerals for atomic energy; a guide to exploration for uranium, thorium, and beryllium, Robert D Nininger, 1954

The uranium-vanadium deposits of the Uravan Mineral Belt and adjacent areas, Colorado and Utah, William L. Chenoweth, 1981

And Now For Something Completely Different