1730: The first prospectors in the the Franklin Mining District, Dutch miners from the Hudson Valley, unfortunately called the area "the copper tract." Although copper minerals do occur in the orebody - 38 of them, including a rare copper hydroxyl nitrate, Rouaite (TL), none of the minerals are in sufficient quantity to be mined for the metal. Zinc is king at Franklin.

By 1770 the "copper tract" was owned by Lord Sterling, above. William Alexander had inherited a fortune from his father, and decided to dabble in mining. An interesting man, big drinker and war hero. He affected to be known as "Lord" Stirling, even though the House of Lords had dismissed his claim to the Earldom. A Major General in the US army during the War of Independence, Lord Stirling was described as "the bravest man in America." His mining enterprise was rather less auspicious, and began badly...

Lord Stirling's miners extracted several tons of cuprite, then known as ruby or red-oxide of copper, and he shipped it across the Atlantic to England for smelting. Unfortunately the ore contained no copper. It wasn't cuprite. The pile of faux copper ore languished, unwanted and unidentified, in Britain. A few specimens went to various English collections, their origin to be forgotten, and later credited to various localities where the new mineral wasn't found.

It wasn't until 1820 that the enthusiastic New York mineralogist, Dr. Bruce, analysed the mineral, and found it to be zinc oxide. He gave the new mineral the name "Red Oxide of Zinc." It became known as "Ruby Zinc" by the miners at Stirling Hill and Franklin. In 1845 it was renamed as Zincite. Large masses of the mineral were found, especially at Sterling Hill, with a specimen exhibited at London's Crystal Palace weighing in at 16400 lbs.

Returning to Lord Sterling in the 1770s, his mineral misidentification problems were not over. He decided to construct a furnace at Franklin to smelt down the black iron ore which was abundant in his mines - magnetite. While it was being constructed he sent a large quantity of ore to his furness at Charlottesburg, at great expense. It couldn't be smelted. It wasn't magnetite.

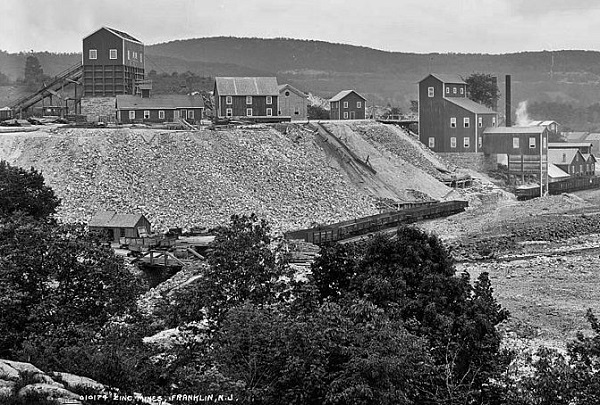

For years the pile of ore lay on the ground unwanted. The new Franklin furnace was unused; by 1819 it was a ruin. But that year the French chemist Berthier analysed the mineral, and found it to be an oxide of both zinc and iron. He called it Franklinite. The zinc content prevented successful iron production in the furnaces. But zinc was considerably more desirable on the metals market... Commercial mining of zincite and franklinite, for the production of zinc metal, began at the Franklin and Stirling Hill mines.

With the discovery of two minerals new to science, the Sterling-Franklin orebody got the attention of mineralogists. Lord Sterling's eyeball-ID of the minerals unearthed from his mines, was replaced by more satisfactory analytical techniques. In 1770 the self proclaimed Earl of Stirling, Billy Alexander, could easily have determined that his ruby copper was dodgy - a simple acid test would not have given any blue or green colour upon reaction, a characteristic of copper bearing minerals. The density would have also been diagnostic (cuprite 6.14 g/cm3, zincite 5.66 g/cm3).

His magnetite similarly could have been discovered as bogus, but only with wet chemistry. The regular checks a mining mineralogist would do in the 1700's would have indicated magnetite. Franklinite is very similar to magnetite, in terms of crystal form and appearance, density, hardness and streak. Franklinite is also magnetic.

Lord Stirling can't be criticised for his mineral misidentification in New Jersey, given that that the minerals he was mining were unknown. On a world scale, the Sterling-Franklin orebody is highly unusual. The orebody contains 376 distinct minerals. 71 of these join zincite and franklinite as being found there first, some of these are only found there.

The identification of this mineralogical diversity has been massively assisted by collectors. Many of the minerals are beautifully fluorescent, and highly sought after. The miners soon realised that the rock they were processing for zinc, had a side value many times the metal price, if it was different from "the run of the mill." Lunch boxes became more heavy at the end of a shift...

Collections were amassed of these Sterling Hill and Franklin mineral treasures. These specimens, under analysis to this day, have provided 73 type locality minerals, with 9 more awaiting approval.

An example of these new minerals is Gerstmannite. It's one of the rarest of the world's known 5402 species. It's named after a collector, Ewald Gerstmann of Franklin, New Jersey.

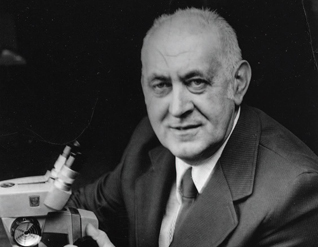

Mr. Ewald "The Dutchman" Gerstmann [1918 - 2005], who worked as a power engineer at a local hospital, was a prolific collector of local minerals. His interest began in 1954, when he purchased some specimens from a miner, for his daughter's science assignment. A collector offered him much more than he'd paid for the minerals, and he decided to find out more about them. The bug had bit. Self taught in mineralogy, over the next 25 years he purchased over 500 private mineral collections, just for the Franklin and Stirling Hill specimens. He also trained and encouraged local miners to be on the look-out for interesting and different specimens.

“My wife thought I was crazy when I spent $100 for a rock,” Ewald Gerstmann, 1956. He created a world-class collection and housed it his museum at Franklin, which was open to the public at no charge. He sent samples freely to any scientific researchers who requested them, and was ultimately responsible for providing specimens that led to the description of over 30 new species.

In 1970 miners came across an odd mineral, at a stope above the 1100 ft level, in the Stirling Hill Mine, Ogdensburg, NJ. In appearance it looked like pectolite. It wasn't spectacular, nor fluorescent. But it was different, and specimens found their way into the possession of Gerstmann. Five years later he got around to having a mineralogist, Paul Moore, analyse the mineral. It was new to science, and was named after "The Dutchman" himself.

Gerstmannite is interesting; not just because of the sums of money paid for fragments from the 1970 (and only) find, see below, but for the zinc silicate’s molecular structure. From this document by P. Moore, "Gerstmannite is an elegant example of a new kind of structure type based on oxygen cubic close-packing."

References:

Analysis of two Zinc Ores from the United States of America, by M.P. Berthier, 1819

On the Red Oxide of Zinc of New Jersey A.A. Hayes 1872

The Minerals of Franklin and Sterling Hill, Sussex County, New Jersey 1934, Charles Palache

Gerstmannite, a new zinc silicate mineral and a novel cubic close-packed oxide structure Paul B. Moore & Takaharu Araki

And Now for Something Completely Different

_____________________