In 1985 I had acquired some palladium metal, as a by-product of some illicit platinum reclamation I was undertaking. I made the above quarter-ounce "nugget" with it, drilled to be worn as a pendant.

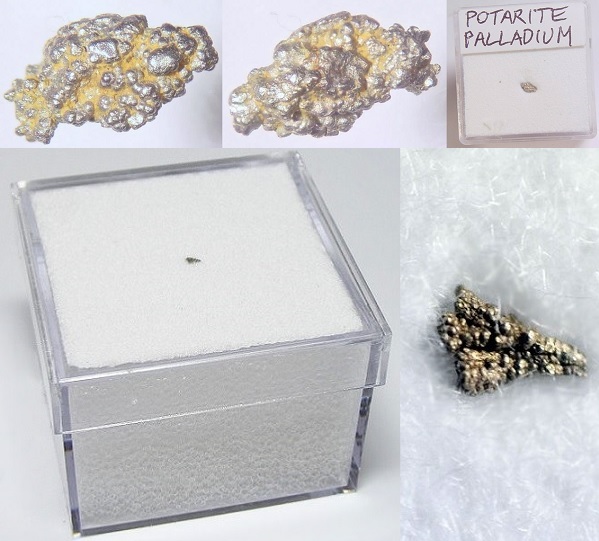

Natural Pd specimens below, from the type locality, Bom Sucesso Creek, Serro, Minas Gerais, Brazil

In this post I'll outline some nuggets of information about the element itself, some of its controversial history, interesting occurrences of the native metal, and the Post Office Type-3000 telecommunications relay.

William Hyde Wollaston's Secret Discovery

The English chemist and physicist William Hyde Wollaston (1766 – 1828)

In 1801 Wollaston was getting heavily into the platinum business. He'd perfected a technique of chemical purification and consolidation of native platina, into pure malleable platinum ingots. In the next 20 years, together with his assistant John Dowse, he produced the world's best platinum by refining 47,000 ounces of native platinum, making 36,000 ounces of malleable pure metal with his chemical and powder metallurgical process.

Above, native platinum from the type locality, Chocó Department, Colombia. Wollaston obtained most of his platina from Colombia, via Jamaica. The platina needs serious refining to produce the quality of platinum required by his customers. Platinum was in demand for laboratory equipment, for boilers in sulphuric acid manufacture, and by gunsmiths such as Manton, who patented "Platina Touch Holes." By far the most of Wollaston's initial sales of pure platinum went to quality gunsmiths.

Although obviously after some serious money, Wollaston was a scientist, and very interested in the residues left over from his refining process. After much investigation, he discovered two new elements and named them Rhodium and Palladium. Normally a scientist would immediately publish their discoveries in one of the learned journals. However Wollaston was initially unwilling to publish. To do so would release trade secrets about his chemical extractions. He was a businessman, and incredibly elected to sell an unknown metal to the public.

The first the World knew about palladium was a single sheet flyer, sent in April 1803 anonymously to scientists in London -

P A L L A D I U M

OR

NEW SILVER

Has these properties amongst others that shew it to be

A NEW NOBLE METAL

1. It dissolves in pure spirit of nitre and makes a dark red solution.

2. Green vitriol throws it down in the state of a regulus from this solution as it always does gold from aqua regia.

3. If you evaporate the solution you get a red calx that dis solves in spirit of salt or other acids.

4. It is thrown down by quicksilver and by all the metals but gold platina and silver.

5. Its specific gravity by hammering was only 11.3 but by flatting as much as 11.8

6. In a common fire the face of it tarnishes a little and turns blue but comes bright again like other noble metals on being stronger heated.

7. The greatest heat of a blacksmith's fire would hardly melt it.

8. But if you touch it while hot with a small bit of sulphur it runs as easily as zinc.

It is sold only by

Mr FORSTER at No 26 GERRARD STREET, SOHO

LONDON

In samples of five shillings half a guinea and one guinea each

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Mr. Forster, a mineral dealer, was Wollaston's front man to sell the new metal. Forster charged a shilling a grain (65mg) for palladium - six times the price of gold! Wollaston hoped to make a few bob, and to induce many scientists to obtain samples, to confirm the discovery of a new element and hopefully create a demand for the metal.

The plan went tits-up when the whole stock was bought by a certain Richard Chenevix. An Irish chemist and mineralogist, known for his sharp cynicism and for engaging in combative criticism, Chenevix thought the new metal was a fraud.

He reckoned it was a man-made alloy of platinum and mercury. Totally wrong, but his results were printed in Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, "Inquiries concerning the Nature of a metallic Substance lately sold in London, as a new Metal, under the Title of Palladium" May 12 1803.

Wollaston responded to this unconventionally. Instead of publishing his work on palladium, he (again anonymously) issued a challenge in A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts - "Reward of Twenty Pounds for the Artificial Production of Palladium"

Soon many of Europe's chemists were trying to make palladium from platinum and mercury à la Chenevix. They were all at it, Vauquelin, W. H. Pepys, Humphry Davy, Valentin Rose, A. F. Gehlen, M. H. Klaproth, and not forgetting Professor J. B. Trommsdorff of Erfurt. They failed.

Wollaston had privately told Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society, that he was the source of the anonymous palladium, and that it was most definitely an element. Despite Bank's knowledge that one of his publications was totally incorrect, Chenevix was still awarded the Copley Medal in 1803 for his various Chemical Papers printed in the Philosophical Transactions. Banks was not at all pleased with the underhand way Wollaston was handling the palladium controversy.

Eventually Wollaston had to publish. He wrote "On the Discovery of Palladium; with observations on other Substances found with Platina" which was printed in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 1805. The following video shows Wollaston's original documents and palladium samples, which he'd bequeathed to the Royal Society -

A Peculiar Property of Palladium

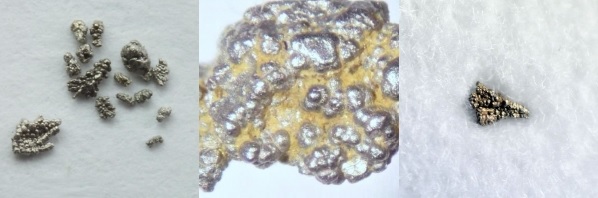

Above, artificially created crystals of pure palladium. When in finely divided form the metal is a superb catalyst, a property which has led to it being in great demand for automotive catalytic converters. Related to its catalytic ability, this platinum group metal also has a quite remarkable property -

Above, artificially created crystals of pure palladium. When in finely divided form the metal is a superb catalyst, a property which has led to it being in great demand for automotive catalytic converters. Related to its catalytic ability, this platinum group metal also has a quite remarkable property -

Palladium metal can absorb 936 times its own volume of hydrogen.

This means that a 1cm cube of palladium metal can absorb or occlude (dissolve?) almost a liter of hydrogen gas! To mechanically compress such a volume of gas to this density, it would have to be pressurised to nearly 14,000 psi.

Palladium absorbs that much hydrogen with ease. All that is required is to use palladium as the cathode during the electrolysis of water. Thomas Graham (1805–1869) discovered that the metal expands considerably when "charged" with the gas. This from atomistry.com -

"This change in volume of palladium during hydrogenation may be made the subject of a pretty lecture experiment. Two plates of palladium foil are varnished each on one side, and immersed in a cell containing acidulated water. On passing an electric current through, the electrode serving as cathode absorbs hydrogen on one side, expands and curls up, varnished side inwards, whilst the anode remains perpendicular. On reversing the current, the curled plate gradually straightens out, whilst the other plate begins to curl. By using a narrow, vertical glass cell, the image may be thrown on to a screen, yielding a very effective demonstration."

Another curiosity of hydrogen charged palladium is that it's a metal which can be set on fire, without itself being consumed -

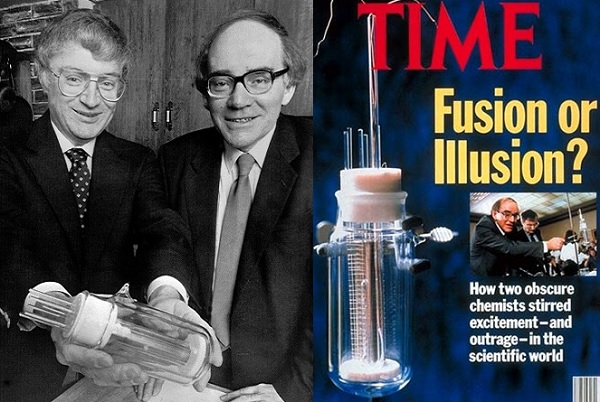

The occlusion of hydrogen (in the form of the isotope deuterium) by palladium was used by Fleischmann & Pons to attempt nuclear fusion, with the resultant 1989 science fiasco -

Returning to things mineralogical, palladium is found in 60 (mostly very rare) IMA-recognised minerals, but here we're dealing with palladium nuggets, perhaps with a diversion into the dendritic crystals of Devon at Hope's Nose.

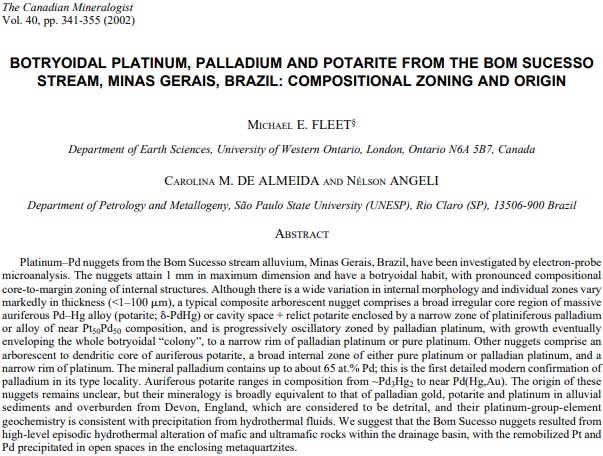

Bom Sucesso Creek, Serro, Minas Gerais, Brazil

The type locality for native palladium, and presumably where H.E. Chev. de Souza Coutinho, ambassador from the court of Portugal, obtained specimens to send to Wollaston for analysis. Wollaston had discovered palladium as an "impurity" in platina from Colombia, but this Brazilian material had discrete small grains of virtually pure palladium.

Among the specimens of Bom Sucesso palladium that has been sold through e-Rocks, here's a couple of examples -

At top, this 3.5 x 2 x 2 millimeter sized specimen (Uravan Minerals) sold for £282. The lower 1 x 1 x 1 mm specimen (Geo-Trader Minerals) sold for £145. These "nuggets" are of a complex mineralogical nature -

The above paper is well worth a look at, the images of sectioned nuggets show the very interesting zoned interiors, with alternating layers of potarite PdHg and platiniferous palladium.

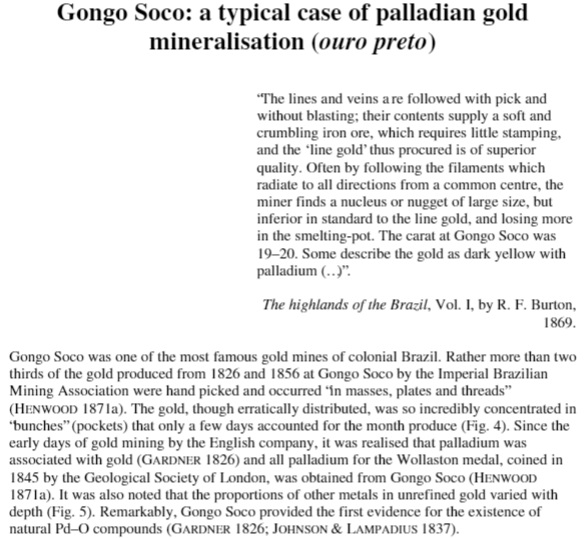

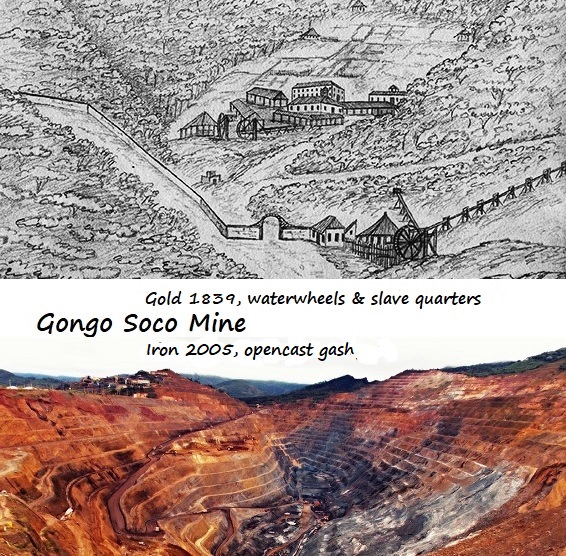

Gongo Soco, Minas Gerais, Brazil

in 1745 a prospector found gold in a stream cutting through the region. The land was later inherited by João Baptista Ferreira de Souza Coutinho, Baron of Catas Altas. He sold it to the Imperial Brazilian Mining Association, based in Cornwall, England, for ₤79,000 in 1825. The wholly British IBMA company soon bought 650 local slaves and sent a squad of 80 Cornish miners over the Atlantic to oversee the mining. They introduced the deep-shaft mining techniques of Cornwall and up to date milling and processing to the slave labour force. They even built a hospital, and cemetery for Europeans only.

This example of typically British exploitation unearthed, from 1826 to 1856, more than 12 thousand kilos of gold. Unfortunately when the first shipments of Gongo Soco gold arrived at the Royal Mint at the Tower of London, the bullion bars were rejected because of their brittleness. The famous platinum refiner Percival Norton Johnson assayed the metal, finding a significant amount of palladium.

Johnson separated the palladium from an enormous amount of Gongo Soco gold, and in 1845 supplied the Royal Geological Society with metal to mint the first palladium versions of the Wollaston Medal, a scientific award for geology, the highest award granted by the Geological Society of London.

Above from Palladian Gold Mineralisation (Ouro Preto) in Brazil: Gongo Soco, Itabira and Serra Pelada, A.R. Cabral, 2003

When the gold ran out, interest was shifted to the matrix rock it was found in - a suite of rich iron ores.

The present-day Gongo Soco mine can be seen in this zoomable view. Precious metals are still recovered from the mine, as tiny palladium nuggets in the limonite. They're very similar to the complex nuggets from Bom Sucesso.

Next, we look at palladium in the United Kingdom. Apart from a huge untouchable bonanza in Cumbria, mentioned later in this article, an area of South Devon has mineralogically similar palladium to the South American deposits -

Hope's Nose, Devon, UK

Minerals from Hopes Nose - Gold, Palladian Gold, and Chrisstanleyite Ag2Pd3Se4 (TL) with Fischesserite Ag3AuSe2, Clausthalite PbSe & Gold.

Below, a Hopes Nose specimen, with the gold digitally extracted from its calcite matrix, using computed tomography.

The Hopes Nose occurance of dendritic gold was described by Sir Arthur Russell in 1929. Later, R.C. Leake et al extracted PGM (platinum group metals) from the alluvium in the general area of South Devon; here's an abstract from one of their papers -

Internal structure of Au-Pd-Pt grains from south Devon, England, in relation to low-temperature transport and deposition

"Microchemical mapping of the gold and platinum-group element-rich grains has revealed a wealth of internal structure that reflects the history of grain growth. The first of four main stages produced dendritic and zoned grains of gold enriched in Pd, gold-potarite or gold-bearing potarite. A second phase comprised deposition of gold with 8wt% Ag in thin, intragranular films and "crack fills'. The third phase produced overgrowths of Ag-enriched gold, which truncated previous growth zones and intergranular films. Minute grains of selenide minerals occur within Ag-enriched gold in overgrowths and intragranular zones. Precious-metal grains are thought to have grown from oxidizing saline fluids at about 100°C."

Later still, in 1998 a new mineral was found at Hopes Nose - Chrisstanleyite Ag2Pd3Se4, a silver palladium selenide. The specimen of this very rare mineral (shown above, 0.7 × 0.6 × 0.3 cm, minerals-online), sold for £202.

We now divert from mineralogy again, to a palladium nugget that would fare rather badly, in any attempt at fraudulently passing it off as a mineral specimen!

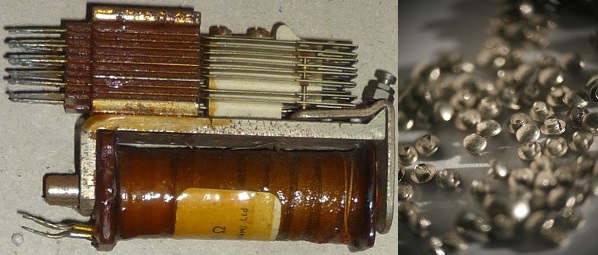

Quarter Ounce Palladium Nugget made from Post Office Relay Contacts

A 1/4oz palladium necklace pendant I made from relay contacts, using an oxy-acetylene torch in 1985. The small palladium contacts around it were left over (2.7g), as I wanted exactly quarter of an ounce for the pendant. You can see the indentations on the contact stems, where I manually punched each contact from its spring. I melted more than required, to allow for the drilled hole, and finally filed it down to nearly the exact weight (actually 200mg over, I was going to polish it). The pendant is 1.7 x 1.2 x 0.7 centimeters and weighs 7.28 grams.

I've always had an affinity with scrap metal. My Uncle Jim was a scrap-man, and from a early age I greatly enjoyed my visits to Jim Curry's scrap yard in Annfield Plain. Anything I found and wanted, after rummaging through the dangerously piled up "stuff" at his yard, he never gave me. I always had to buy it - he was a shrewd character, instilling in me the value of scrap. Oddly, nothing seemed to cost more than a fraction of my meager pocket-money!

I got retort stands and clamps, a high-voltage magneto, half a dozen WW2 RAF Spitfire G45 gun cameras, a RAF Gyro Gun Sight recorder Mk 2, a large photomultiplier tube complete with thallium doped sodium iodide crystal from a scintillation detector, amongst many other treasures. When my chemistry skills had progressed from lethal pyrotechnics into analysis, I remember helping him with his industrial scrap, identifying silver from contactors, nickel and zinc. He would have loved to get a scrap telephone-exchange!

Many years later (in 1985) I was working as a test equipment development technician at GEC Telecommunications in Aycliffe. Noting that all the telephone testing equipment throughout the factory used a GPO 3000 series relay inside them, purely as an inductive load, I reasoned their unused contacts could be "liberated." Especially since some were made of platinum....

The GPO 3000 series relay carved in stone - a detail of one of the keystones above windows in the Faraday Building, London.

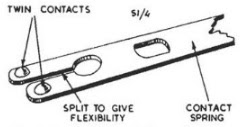

I got the OK from my boss to remove all of the contact springs, as I was at the time adding a modification to all the testers in the factory. Two tiny contacts were swaged on to each bifurcated nickel-silver spring -

The contacts were made from either platinum (Pt, contacts as rare as Turin Shroud offcuts), palladium (Pd, much more common, but still rocking-horse excrement scarce) or silver (Ag, most of them, comparatively worthless, common as pig muck). I was after the platinum. As you can see from the graph below, Pt was worth much more than Pd 30 odd years ago, a situation that has now reversed!

The springs with platinum contacts were easily identifiable by a small notch on the springs. In order to separate these contacts from the springs, I went to the workshop with the problem. The lads there, John, Gordon & Mr. Modo, soon made me a hand operated tool for the job. With it I could punch out the tiny contacts, one by one. My break times were then consumed by contact removal.

Word soon got round about what I was doing. A boss came to see me to tell me that a couple of large telephone-exchange relay-set racks had been scrapped off, and I was welcome to get what I wanted, as they were to be sold off as general scrap. These racks contained hundreds of relays. It took a week or so of graft, removing the spring sets from the relays on my dinner hours and breaks. After that I continued with my manual platinum contact removal. It took a long time. I recovered over two and a half ounces of platinum! Which I had a plan for....

I had a huge sack of non-platinum contact springs left over. At this point I was completely knackered. Working without breaks for weeks does even a twenty-odd year old no good at all. I can't be arsed, I thought..... But uncle Jim wouldn't let these go, I reasoned..... The palladium contacts were worth my time, I decided.

Unfortunately palladium contacts are indistinguishable from the more common silver contacts. That is, without deciphering the serial number on the relays, which of course I'd never done. So I obtained some hydrogen sulphide solution from the GEC chemilab and just dumped it into the poly-sack for a few days.

The smell off this was very bad when I opened it. Worse than Doddsy's mam's kitchen. But it worked. All the worthless silver had gone black. Nobody came anywhere near me while I sorted the palladium springs; during the process, or for the rest of the day(s). H2S is not just the quintessence of rotten-eggs, it's lethal stuff. One breath of the pure gas and you're brown bread. But it reacts very readily with (relatively worthless) silver metal, to form black silver sulphide. But leaves precious metals like palladium shiny.

So.... I had my many hundreds of palladium contact springs, and began to pop the contacts out. I quickly gave up, reasoning that the metal wasn't bloody worth it! I already had my 2.5 oz of platinum; once I'd weighed-in the metal, I could afford the air-fare to Los Angeles and have a laugh. In the meantime I wanted to enjoy my work-breaks with a cup of tea and a bacon-butty again, and go to the pub at lunchtimes. So I just dumped the remaining Pd springs (worth thousands now) into the metal-scrap skip. :(

Getting my precious metals out of the GEC factory, without breaking the law, was easy. My boss, being amused with my fortitude, resilience and determination with the mind & hand-numbing project, done in my own time, and using stuff that would have gone for pennies to a scrap merchant, signed a chitty - "Relay parts, scrap. Less than 1lb. Value £0."

Lots of anxiety; I approached the security guard on leaving one night, offering him the chitty and my little box containing a couple of dismantled GPO 3000 relays and brown paper wraps with the contacts in. After a cursory glance at the box, he took the chitty, waved me on, and said, "Enjoy LA Rog."

The platinum was weighed-in by post to a company I found in Exchange & Mart. I started to have meaningful breaks (smoking tabs and drinking tea) at the telephone factory again. In the few months before I moved to California, I found time to melt down some of the palladium I'd half-heartedly removed, into the nugget this 31 second video shows -

I used my mate's oxy-acetylene rig on a chemistry-lab charcoal block, which I'd previously used only for analytical blow-pipe work. Pd melts at 1554.9 °C. When I drilled out the hole for the leather bootlace I used as a "necklace," I saved the swarf, but the little bag went walkabout a couple of decades ago :(

I was in a weekly Channel 4 television programme called "Families" at the time I made the palladium nugget, here's a still from the '85 VHS video tape, which shows me wearing the Pd pendant. What a tosser.

We end with a last titbit of Pd miscellanea. The total amount of palladium on planet Earth is increasing....

A single 1000-MW nuclear power plant produces about 27 kilograms of brand new palladium per year. It is created from the fission of uranium. There's around 450 reactors worldwide.

Unforunately fission palladium contains about 15 per cent of the isotope Pd107, which is a mildly radioactive beta emitter. A tad unsuitable for car exhausts, this growing fortune (how many precious metal dealers use a geiger counter?) of precious metal languishes, unrefined and unwanted, in glowing blue pools around the world.

Below, a 60 year old spent fuel pool, the infamous open air B30 pond at Sellafield. It's 78 miles from my home, and tempting though the hundreds of kilos of palladium are, the illicit reclamation of this bonanza from the other (very highly radioactive) fission products, is more problematical than from PO Type-3000 relays. The blue glow is the luminous electromagnetic shock waves produced by particle radiation traveling faster than light in the water - Cherenkov radiation. Note the seagull....

References -

On the Discovery of Palladium; with observations on other Substances found with Platina, William Hyde Wollaston, 1805

Inquiries concerning the Nature of a metallic Substance lately sold in London, as a new Metal, under the Title of Palladium. Richard Chenevix, 1803

Reward of Twenty Pounds for the Artificial Production of Palladium, A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts, 1803

On platina and native palladium from Brasil, William Hyde Wollaston, 1809

Palladian gold mineralisation (ouro preto) in Brazil: Gongo Soco, Itabira and Serra Pelada, A.R. Cabral, 2003

Botryoidal Platinum, Palladium and Potarite from the Bom Sucesso Stream, Minas Gerais, Brazil, Fleet, de Almeida & Angeli, 2002

On the Occurrence of Native Gold at Hope's Nose, Torquay, Devonshire. Arthur Russell, 1929

Exploration for Gold in the South Hams District of Devon. Leake et al, 1992

Gold and Platinum Group Minerals in Drainage Between the River Erme and Plymouth Sound, South Devon. Leake et al, 1990

Internal structure of Au-Pd-Pt grains from south Devon, England, in relation to low-temperature transport and deposition, Leake et al, 1991

A new mineral, chrisstanleyite, Ag2Pd3Se4, from Hope's Nose, Torquay, Devon, England. Paar et al, 1998

GPO 3000 series relay - a source of precious metals. Lateral Science, 2018

Thenard 1832, "Animals when allowed to breathe the pure gas fall down as if struck with a bullet", Lateral Science, 2012

And Now For Something Completely Different