Taking two of the minerals, galena and bismuthinite, we’ll look at their occurrence in the North Pennines, and then (accompanied by a 13.5 carat slice from a flawless and ice-clear diamond) their occurrence elsewhere.

Bismuthinite

One day, when Cambokeels mine, Weardale, was still in operation, my Dad & I spent an hour or so on the spoil-heaps, before going up to Heights mine. We found some nice chalcopyrite crystals and light green massive fluorite which was light sensitive and lost its colour as you watched. I remember picking up a 5 x 4 x 2 cm drusy quartz (1mm points) which was pretty, in a sparkly sort of way, but not of any great interest. This specimen languished in my collection, unappreciated, until five years ago.

A friend had mentioned that his niece was interested in minerals, so I began sorting through my rocks for a small collection to give her. I'd recently bought a stereo microscope and had a quick look through the specimens I'd put together. The Cambokeels drusy quartz looked quite spectacular under the scope, but the underlying quartz matrix proved much more interesting. Fine grained, almost chalcedony-like in parts, with cavities a few millimeters across having minute, but beautiful clear quartz prisms, some doubly terminated. A few scattered chalcopyrite crystals. Then I noticed the presence of filiform needles of what I assumed was millerite, a mineral I was acquainted with, from its rare occurrence in the Namurian shale ironstone nodules at Coldberry Gutter, Teesdale. However the crystals' appearance and paragenesis was different - in that they were a steel grey/blue, as opposed to brassy millerite, and they were included inside the quartz.

Millerite in ironstone nodules was the last mineral to crystallise - you can open a nodule and a breeze can blow the crystals away, I lost my best millerite spray some time ago, collecting when the Gutter was acting as a wind tunnel! The very fine needles in the Cambo specimens had formed before the quartz, were present running through the massive quartz, individual clear quartz prisms and free standing to a couple of millimeters into tiny cavities.

Referring to the Cambokeels Mine page on Mindat, I found no mention of millerite, but bismuthinite is noted (no photos though), and then I found this fascinating article in Mineralogical Magazine -

Bismuth-bearing assemblages from the Northern Pennine Orefield, by R.A.Ixer, B.Young & C.J.Stanley. Mineralogical Magazine, April 1996, Vol 60, pp. 317-324. Online here.

The descriptions of the bismuthinite crystals, and associated unidentified bismuth mineral globules, was exactly as I saw through the microscope in the specimen I'd been about to give away! -

"Cambokeels Mine free standing acicular crystals [of bismuthinite] up to 1 mm long grow out from the surfaces of euhedral quartz crystals lining vugs in quartz-rich veinstone."

Soon I'd reduced this specimen into fragments, and I now have some lovely micromounts of a mineral I'd never before collected, and hadn't even realised was present in the specimen, or indeed Weardale!

I replaced the pretty drusy quartz gift (which I'd bashed to bits) with a better looking specimen (to the naked eye) of green fluorite from Heights, so my mate's niece didn't lose out. It was a win - win situation, especially after I sorted through the dust and tiny fragments from my reduction frenzy, as I found a perfect chalcopyrite octahedral crystal and some doubly terminated quartz floater assemblies (one with an included bismuthinite crystal) of great beauty.

Hughes Buys Diamond for NASA

Hughes Buys Diamond for NASA

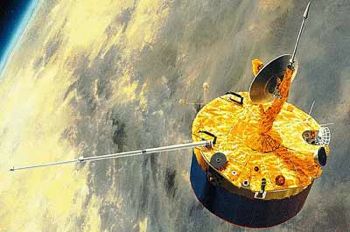

A diamond window, 18.2mm in diameter, was specified by NASA in 1977 to be fitted to the Large Probe of the Pioneer 13 spacecraft. The Hughes Aircraft Company were building the Pioneer Venus Multiprobe, and subcontracted D. Drukker & Sons of Holland to cut and polish the diamond, above left. The flawless, precisely dimensioned disc of natural carbon was fitted into a tungsten mounting, right.

Pioneer 13 was launched by an Atlas-Centaur rocket in 1978. Soon after, a switched-on accountant requested the return of the import duty that Hughes had paid when the diamond had been flown over from Holland, some $12,474. The reason being that the item has been exported, country of destination, Venus. The US Customs Service coughed up.

NASA’s Pioneer Venus Multiprobe. The four atmospheric entry probes have just released from the “bus.” All probes had diamond and sapphire windows for their instruments.

The diamond performed perfectly when the Large Probe, a 1.5 m titanium sphere, plunged into Venus’ thick carbon dioxide atmosphere. It suffered 500G deceleration from 25,850 mph, a 55 minute descent through clouds of highly corrosive sulphuric acid, and pressures so great (93 bar) the atmosphere is supercritical. Room temperature on Venus is 467 °C. Only diamond could withstand such conditions, and still be perfectly transparent to the atmospheric infrared radiation the probe’s radiometers were measuring.

The 13.5 carat diamond has only a tenuous link to the galena and bismuthinite story however. More relevant is the surface mapping radar on Pioneer 12, another spacecraft launched three months before the Pioneer Venus Multiprobe.

As Pioneer 13 dropped its 4 probes, Its sister vehicle Pioneer 12 ( Pioneer Venus Orbiter, above) was mapping the surface of Venus with its 1.757 GHz radar. It showed something quite unexpected.

The Orbiter’s Surface Radar Data

As well as doing its thing, range finding to map the topography of Venus, the radar measured the reflectivity of the surface. Quoting NASA, “These measurements showed unusually high values of Fresnel reflection coefficient (approaching 0.40 in extreme cases) that are associated with many of the elevated regions of Venus.” In other words, the highlands of Venus reflected the radar so well, it was as though they had an almost metallic covering. Something with a high dielectric constant was reflecting the 1.757 GHz radar signal.

Venusian Snow

On the lower plains of Venus, sulphide minerals are vapourised because of the ambient temperature, 467 °C - not far off red hot, which is visible from around 525 °C. Using the earth’s fumarole data on volcanic sublimates, it was determined that as temperatures fell due to elevation, lead sulphide and bismuth sulphide would crystallise from vapour at the altitude the reflectivity began. This means it snows galena and bismuthinite on Venus! Together with a handful of sulphosalts such as cannizzarite (type locality- fumaroles at La Fossa Crater, Vulcano), the reflective mountains of Venus are explained. Is there glacial activity on Venus? And what about the hoar frost…… ?

Sublimated metallic sulphides; cannizzarite, bismuthinite, lillianite & galena

La Fossa crater fumaroles, Vulcano

Mineral Collecting

Of interest is that the “snowline” at 2600 metres altitude, is at the same point that the atmosphere reverts to a gas, from being supercritical over the lowlands. Given metallic sulphides ability to grow spectacular crystals, one wonders at the possible large crystal assemblies that could grow (in sheltered areas) on the highlands of Venus at such a diffusion interface…..

e-Rocks looks forward to marketing mineral samples brought back from future commercial exploitation by Elon Musk --

“Pristine unoxidised lustrous crystals of cube-octahedral galena, up to 80cm, with sprays of bismuthinite to 50cm adorn this huge museum-quality Venusian specimen. Also, providing contrast, are areas of perfectly crystallised nests of galenobismutite, lillianite, cannizzarite, and cosalite crystals to 16cm. Recovered 2022 from Maxwell Montes, Venus, by Musk Minerals.” Starting price $10m.

Attn. Mr. Musk, “I’ve got my 30 year old Estwing hammer Elon, in a plaggy bag with some some old newspapers and four cans of Fosters, and I’m willing to travel…..”

References:

Volatile transport on Venus and implications for surface geochemistry and geology. By Brackett, Fegley, & Arvidson

Investigating Mineral Stability under Venus Conditions: A Focus on the Venus Radar Anomalies. By Erika Kohler

Vapor Transport, Weathering, and the Highlands of Venus. By Brackett, Fegley, & Arvidson

"And I work well under pressure..."

And Now for Something Completely Different

A Day in a Ceylon Gem Field, 1933 Joseph L. Gillson

Identification of diamond in the Canyon Diablo iron. 1939

C.J. Ksanda and E. P. Henderson

___________________